Introduction

Although Islamic finance forbids interest, the reality is far more complex. Around 90% of global Islamic banking assets are still priced at interest-linked benchmarks. This post explores how that came to be, what it means for the industry’s integrity, and whether true reform is possible

In general, I am pleased to see that the topic of Islamic banking, or Islamic finance (whatever we want to call it), appears to be more visible as time goes on. By being more visible, I refer to the following types of things:

- The global industry is growing. It has grown from $200bn (back when I first started) to over $2 trillion now

- It is becoming more established in “core” countries. In the GCC, and Malaysia, Islamic banks are now well established and part of the banking landscape. They attract not only Muslim customers, but also appeal to the non-Muslim sector too

- Islamic banks offer more products now – rather than just being able to place deposits and apply for home financing, Islamic banks are now offering much more sophisticated products to their customers.

An Islamic bank that does not offer the following will be seen as lagging behind the market

- several types of savings account / term deposits

- a whole raft of credit cards to choose from

- personal financing

- car financing

- home financing

- Investment products, and so on

Islamic banking has spread to new countries and global areas, including both Muslim countries and also to non-Muslim countries (UK, countries in Europe, Asia, South America).

These are, in general, good and positive things.

There is also significant alignment between Islamic economics/philosophy and activities that have grown in popularity over the last decade, such as socially responsible investing (SRI), social investment, impact investment, green or ethical investing. These seek to combine financial return along with a positive social and environmental impact.

Developments in technology also are leading to discussion with regards to how this is compliant (or not) with Islamic principles. Areas such as blockchain, cryptocurrency, smart contracts are all areas that merit discussion and investigation.

However, when we look at Islamic banking (or Islamic economics and so on), it is important to distinguish where we want to be (or where we think we can reach) from where we actually are.

This is important – more than that, I would say an ignorance of where we currently are is symptomatic of something else. Quite what that is, I am not sure, but I hope to shed some light on that here.

Islamic banking is being practiced today, and in quite large volume. In comparison to the global financial markets, the size of the Islamic markets is still quite modest (estimates place Islamic markets of being in the region of 1% of global markets in terms of size) – however, growth has been quite impressive. This growth can be expected to continue, in some form at least.

This should be a cause for all Muslims to feel good – after all, Islamic banking is a crystallisation of an aspect of our faith (rules and principles relating to Islamic commercial and economic law). Hence, its success can be seen as some form of vindication that these principles are good and sound.

In some ways, it serves as a beacon, in a time when there is much social and political discourse about Islam and Muslims on a global scale. Islamic banking is something that many parts of the non-Muslim world are keen to learn about, and perhaps implement or support in some way in their countries.

It provides a keen and powerful counterpoint to a view that has been growing over the last decade – that banking (and capitalism in general), for all the positives it claims to deliver, also brings along with it many unsavoury consequences.

It is not difficult to hold the banner aloft and claim that “our” system is different to how the rest of the world views money and business. Yes, of course we want to encourage business and growth and profit, but it must be done in a wider environment that is built on holistic values.

Transparency, equality, justice, care for others. These are terms that are bound to impress those that hear them. The banning of interest because it is seen as immoral. This is a stance that will attract much support (apart from those that benefit from interest and debt).

We say all the right things, don’t we?

However, we have another way that we can measure the impact and nature of Islamic banking. We do not have to just rely on buzzwords and sound bites.

We have reality that we can measure.

We have a sector that is worth over $2 trillion. We can take a look at what makes up this value. And then we can assess how this activity and value corresponds with what we hear about Islamic banking.

This is not a short endeavour. However, I believe there are some low hanging fruit that can help us begin.

Is Islamic banking purely a sector that is to do with banks? That is a good first question.

The answer should be “not necessarily”. Certainly, we have Islamic banks, and some of them are quite large. Combined, they can be expected to make up a portion of the global sector that is non-trivial. However, business occurs and assets are created outside of banks, too.

Money is invested (always, of course, aligned with our values and principles), assets are bought and sold, business is generated – these activities can occur outside of the banking sector.

It had never been very clear to me how this global size of the Islamic banking sector is calculated. I think we can obtain a fair idea of this if we look at the components of the global (non-Islamic, also called conventional) finance sector.

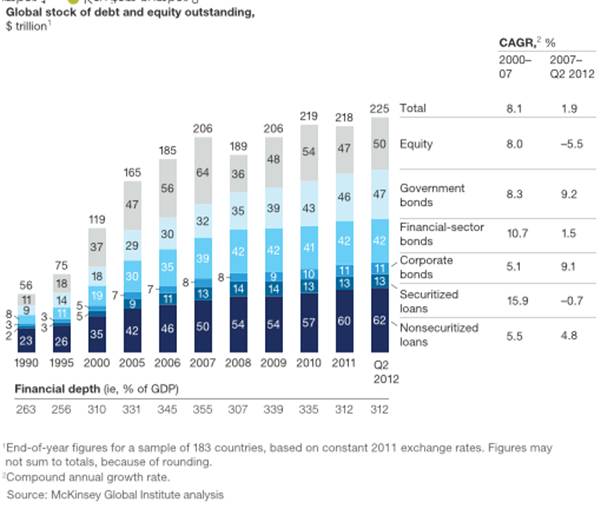

Mckinsey Global Institute produce some data of global financial assets (admittedly this goes back to 2012 but I think it serves to make the points that we need here):

Some interesting things to note:

- the size of the global financial assets is (or was, back in 2012) roughly 100 times larger (at $225 trillion) than the current estimate size of the Islamic banking markets.

- apart from the equity markets, the balance of the assets comprises of debt

- the global markets demonstrate leverage in the region of 78%

- the Mckinsey report calls this “unsustainable” and that it “propelled much of the financial deepening that occurred before the crisis.”

- financing for households and corporations (not specifically detailed in the image above) “accounted for just over one-fourth of the rise in global financial depth from 1995 to 2007.” The report goes on to say this is “an astonishingly small share, since providing credit to these sectors is the fundamental purpose of finance.”

Well, now that we have some idea of the composition of global financial assets, let us return to the Islamic banking sector.

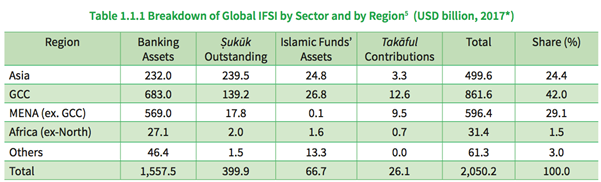

We can find very useful data in the following publication: “Islamic Financial Services Industry Stability Report 2018” released by the Islamic Financial Services Board, one of the most prominent bodies in the sector in the world.

We can see a table that provides a breakdown of the composition of global assets in 2017:

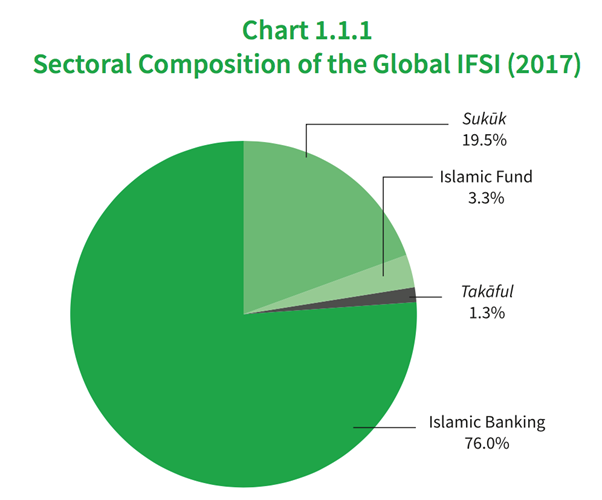

We can see that banking assets and Sukuk outstanding make up the majority of all assets. This is represented in a pie chart in the report:

So, we can see that Islamic Banking comprises 76% of total assets, and that Sukuk comprise 19.5%. Together they comprise 95.5% of total assets.

This corresponds with some other (but perhaps a little older) data that I have previously seen.

So, if we want to get a (very) good idea of what activities are being undertaking in the name of Islamic banking, we need to analyse the assets associated with Islamic banking and Sukuk.

This is clear.

Islamic Banking

Islamic banking assets, here, are simply the sum of total assets of all Islamic banks.

So, what do Islamic banks do?

In the same report by IFSB, there is a section on Islamic banking in Oman. The report states that “Total assets of the IBEs stood at RO 3,484 million as of 30 June 2017, of which financing constituted 77.8%”.

(“IBE” here stands for Islamic Banking Entities.)

Let’s think about that for a second. This is saying that nearly 78% of all Islamic assets in Oman are financing assets.

It is not clear to me at the moment if the overall figure of Islamic banking assets of RO 3,484 includes assets such as Islamic funds and Takaful and so on. If it does, then the percentage of all assets in the Islamic banks that are financing will be higher than the stated 78% (given that funds and takaful are reported to banks separately in the breakdown of data of Islamic banking assets).

And I have to say I find this figure of 78% a little conservative, I have conducted my own detailed analysis of the financial statements of several large, established Islamic banks. My own research informs me that, if we consider the percentage of banking assets and banking liabilities of those banks that are financing assets (and liabilities) then we see figures of between 85%-95%.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: In the last few days, my estimates were questioned and I was told they are “highly inaccurate”, I decided to do some more research and look at the balance sheet of a significant Islamic bank based in Malaysia. What I discovered (and expected) is that my estimates are around 90% of the assets (and liabilities) of an Islamic bank are priced at interest still holds. In fact, in this instance my estimate was prudent – for this bank a figure of 98%-99% is more accurate.

This means that of all the assets and liabilities in these Islamic banks, 85%-95% of these relate to financing.

That may not be surprising to anyone who has some understanding of what banks do, of what the nature of banking is. They exist to provide finance. This is debt.

Let me clear at this stage – debt is not prohibited in Islam, It is certainly permissible for me to provide a loan to anyone, if I so wish. However, I can not charge interest on this.

This, of course, is forbidden.

So, when Islamic banks provide finance, how on earth do they do it without charging interest?

This is a fascinating and deep topic. It needs a lot of space to be covered in sufficient detail. The banks use various contracts such as Murabaha, Mudarabah, Ijara, Musharakah, and Wakala to provide debt to their customers, and to accept deposits. These are not contracts that are designed for debt and interest. These are contracts designed for :

– the buying and selling of assets (trade)

- investment

- enterprise

- some form of collective sharing of risk in ventures

- appointment of an agent to conduct activities on behalf of investors

There is no mention of interest here. The methodology and mechanisms whereby such contracts are systematically dismantled and reconstructed in order to deliver interest is another fascinating topic for another day.

However, there is one aspect of this Islamic debt that can not be disputed.

Every single contract in Islamic banking that serves to deliver debt is priced at interest.

This does not mean the contracts state:

“I will provide a loan to you and charge you 3.4% interest”

Nor do the contracts state:

“I will provide a loan to you and charge you LIBOR plus 200 basis points” – because that is just another way of charging interest (in this case, floating rate instead of a fixed rate).

No, we can not simply charge interest on loans.

What occurs, instead, is that a sequence of events is engineered such that the economic and risk outcome is exactly the same as if the contracts said exactly what they can not say.

Murabaha is used to deliver financing to clients and charge them exactly the same amount (%) of “profit” as the contract that would state :

“I will provide you a loan and charge you x% interest”.

The other contractual forms are used for precisely the same thing. Whether the underlying contractual form is:

Ijara (leasing)

Mudarabah (investment management)

Wakala (agency/ investment management)

Musharakah (partnership and investment)

And so on, the economic outcome is always the same as that of providing loans at interest.

But of course, contractually it appears to no longer be interest – it is “profit” achieved via the trading of assets, or via some engineered form investment or leasing.

Some will say (and many do) that it does not matter if the outcome is the same as that of debt and interest – the form is different – the form is indeed Shariah compliant.

That is a point that I will not argue with here.

My point is this – around 90% of the assets and liabilities of Islamic banks are priced at interest.

Is nobody shocked by this? Maybe, maybe not.

Sukuk

Let’s not forget that Islamic banks are not the only constituents of global Islamic banking assets. Certainly, they are the largest portion, being 76%.

However, 19% of the sector comprises Sukuk.

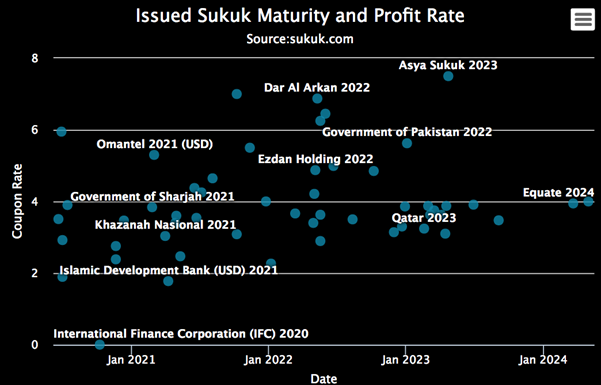

This requires an even shorter analysis – every single Sukuk (that I have seen, and that I have analysed) is priced at interest.

I have not seen a single exception to this. This is true regardless of the underlying contractual structure used for the injection of assets. Some of the popular contractual forms used for Sukuk are:

- Ijara

- Mudarabah

- Wakala

- Murabaha

- Hybrid Sukuk

- Istisna

- Salam

and so on.

In each of these cases, regardless of the contract, the profit that is delivered to Sukuk holders is priced at interest.

The pricing is very clear: we just need to look at the front page of www.sukuk.com:

The left-hand column shows the coupon (or profit rate) or each Sukuk.

It appears that we, as an industry, no longer feel that we need to hide the fact that we are pricing this at interest. Just in case some of us might not be aware of what a coupon is, in banking terms, we can find a definition quite easily:

Investopedia: A coupon is the annual interest rate paid on a bond, expressed as a percentage of the face value. It is also referred to as the “coupon rate,” “coupon percent rate” and “nominal yield.”

- Wikipedia: A coupon payment on a bond is the annual interest payment that the bondholder receives from the bond’s issue date until it matures.

- The Financial Times: The rate of interest paid on a bond

- The Wall Street Journal: Coupon is another word for the interest rate paid by a bond

- The BBC: Investors also receive a pre-determined interest rate (the coupon) – usually paid annually.

The point is clear – the coupon is an interest rate, and it is quite correct to call the profit rate – or periodic distribution amounts of any Sukuk – a coupon.

Again, there is a debate as to whether there is anything wrong with paying an amount that looks like interest, but is the result of legitimate investment and trading, to investors.

However, the very clear point remains that all Sukuk are priced at interest.

Hence, if we assume that 90% of the assets (and liabilities) of Islamic banks are priced at interest, then we can say that around 91.7% (being 90% of 76% and then adding 19.5% for Sukuk) of all Islamic banking assets are priced at interest.

In reality, it should be a bit higher, because we have not yet considered Islamic funds, which comprise 3.3% of all Islamic banking assets. Some of these funds, of course, will be priced at interest. For example

- money market funds

- fixed income funds

- Sukuk funds, and so on.

So, of the total of (approximately) $2 trillion or so of Islamic banking assets, around 90% of these are priced at interest.

I have talked in quite some detail (on my blog, in my books) about how these products are structured and delivered to the markets, and I will continue to do so in the future.

I reiterate, this is not about entering into a discussion about whether it is a good thing or not, that we price at interest. Whether this is permissible, or not. That is a qualitative discussion with many nuances, and allows the presentation, and defence, of any number of stances across the whole spectrum of permissibility.

However, this particular aspect is not subjective. It is not really a matter for opinion (only to the extent of what the actual number is of course –my estimate is 90% and to me it sounds very reasonable based on market data and my own analysis and experience of working in the sector for a long time).

Beyond the somewhat subjective views of whether the figure is 80%, or 90% or 95%, the following is indisputable:

The vast majority (approximately 90%) of all assets in the Islamic banking sector are priced at interest.

For a sector based on principles, rules, ethics, values, transparency, justice, morals and an impressive belief system, and that forbids interest (there is no meaningful disagreement globally that interest is forbidden in Islam) it appears we are not doing very well at avoiding interest.

Some will say that it is reprehensible that we are replicating interest, and others will say it is perfectly fine, as long as the contractual forms are permissible and no superficial commercial rules are broken.

Others will say that it is a little regrettable, but unavoidable due to the pressures of operating in a global economic environment that prices debt at interest.

The scholars who do permit Islamic contracts such as Murabaha to charge profit (that is benchmarked to interest) tend to agree that it is better if this was not the case. Exceptions are made on the basis of necessity. However, the sector should continue to make strenuous efforts to develop products and contracts that do not rely on interest.

But how strenuous can these efforts have been if 90% of everything we do is still priced at interest?

My final point on this topic (for now) is this – regardless of our view on the rights and wrongs of pricing at interest – we see a very interesting consequence of this. I am referring back to the classic contractual forms that I have mentioned above. They are not designed for interest. But they are utilised to enable the paying and receiving of interest.

This adaptation of these classic contracts is an exercise that has consequences. And it is these consequences that really puts to the test our claim that Islamic banking is (or rather, should be) transparent and fair, and based on real enterprise, genuine trading, and the sharing of risk and profits.

This is a topic I will write further on shortly.